Countless programming languages exist today to run fast (and optimistically safe) programs on a GPU. These range from languages in the C family with directives to (mostly) functional languages that veil the low-level details of the hardware. A GPU excels at executing tasks that share a common principal: massive parallelelism. This includes scientific computing, graphics processing, and machine learning.

If the task cannot be parallelized sufficiently, then a CPU wins - it is the jack-of-all-trades of computer hardware. Many programming languages exist today to harness the potential of a CPU. Typically, these languages need to make trade-offs between three aspects: safety, performance, and productivity. This is depicted as a triangle, where the three aforementioned characterizations are placed at the vertices. Then, programming languages are placed somewhere along (or even in) the triangle to demonstrate what influenced their design.

We define safety as a measurement of how correct the program is, for some definiton of correct. This definition could be “memory accesses are always legal” or “this program is formally proven to be correct under some set of axioms.” We use performance to quantify the amount of work accomplished by the program. Typically, as a language provides more and more abstractions to obfuscate the complexity of a CPU, it will emit less performant code. Contrary to what one might think, performance might not always be a primary concern. Running a program in 0.1 seconds versus 0.01 seconds is an order of magnitude difference, and yet likely unheeded for a student who wants to plot a graph. Lastly, productivity is a function of the additional cognitive exertion required to reason about a program and it’s objective(s). Even putting aside the grandiose debate on syntax, this is likely the most subjective. For example, a CPU performance engineer might claim C as the most productive language because it can easily be mapped to the compiled machine code. On the other hand, a Machine Learning (ML) scientist would avow Python is their tool of choice given the wide array of ML frameworks available - a model can be written in 10 lines of code instead of 10,000! There is no ubiquity in the definition of productivity, and that’s OK, so long as we characterize it before arguing one language is more productive than another.

This post isn’t about CPU programming languages, however. Instead, we’ll focus on programming languages that can, by means of compilation or interpretation, run on a GPU. Many such languages exist, e.g., CuPy is a GPU-powered version of Numpy, which allows users to ignore benign terms like “block size” and “thread index”. The CUDA C language is a performance engineer’s best friend (for NVIDIA GPUs, at least); it has perilous control over instruction selection for compute-bound kernels and the memory hierarchy for memory-bound kernels. In between these exist a range of languages, that attempt to provide some equilibrium between safety, performance, and productivity.

The △ of GPU Programming Languages

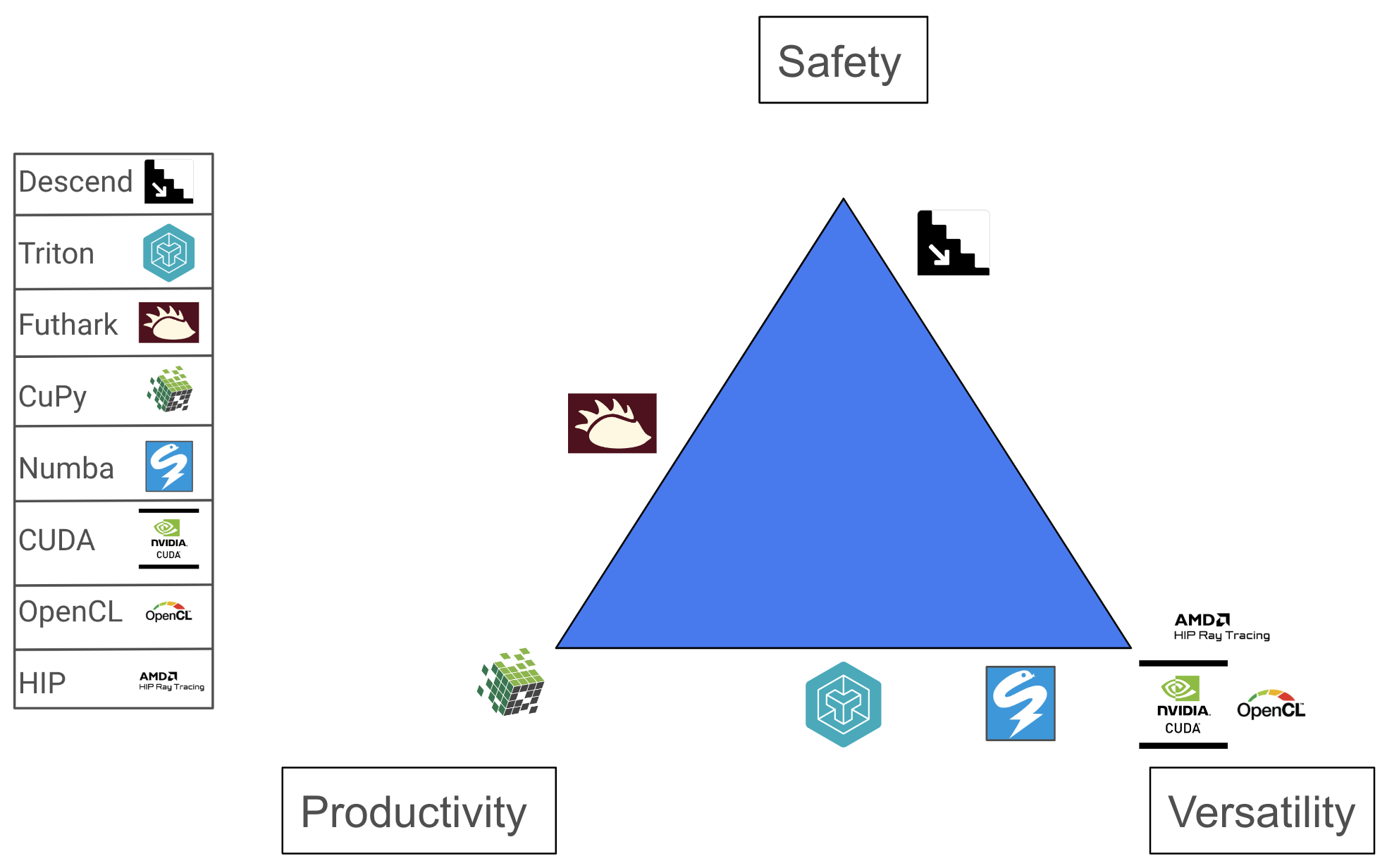

GPUs are specialists - they perform well for embarrassingly parallel problems. The definition of safety remains unchanged: our programs should produce a correct output, for some definition of correct. On the other hand, performance is a key component of GPU programming languages. This is exemplified by the escape hatches even high-level GPU languages provide to squeeze out more performance, e.g., CuPy, a high-level Python framework, provides an API to access low-level CUDA instructions and Futhark, a purely functional array language, has additional semantics for in-place array updates. Therefore, we’ll assume that all GPU languages want to produce performant code, and, if it cannot, it is not useful. We’ll instead define our second vertex as versatility, a metric of how much control a user has over the GPU. Intuitively, writing directly in PTX would provide the most versatility. A more versatile language can do everything a less versatile language can do, at the cost of verbosity and complexity. Moreover, a more versatile language will always be able to write at least as performant programs as less versatile languages. Lastly, we define productivity as a function of the cognitive exertion required to reason about the GPU programming model. Mental capacity is finite; ideally one could focus solely on the algorithm and not have to think about the innards of a GPU.

We’ve now defined the three vertices of a GPU programming language triangle. We have a selection of languages spanning both industry and research, which are specific to GPU hardware: Descend, Triton, Futhark, CuPy, Numba, CUDA, OpenCL, and HIP. Consider the new triangle below:

These placements assume someone is trying to write efficient GPU kernels, and we acknowledge they are entirely subjective. We’ll spend the rest of this post providing examples of different languages, and finish with a slightly deeper dive into the Triton language.

A Few Examples

In an attempt to justify the language placements above, we provide a few examples of matrix multiplication C = A @ B, the defacto standard for high performance computing. Consider the code sample below, written in Futhark:

-- (Written in Futhark v0.25.15)

def matmul [i][k][j] (A: [i][k]i32) (B: [k][j]i32) : [i][j]i32 =

map (\Ai ->

map (\Bj ->

reduce (+) 0 (map \(x, y) -> x * y (zip Ai Bj)))

(transpose B)

)

A

This programming language does not allude to threads, blocks, or memory - instead, the user relies entirely upon the compiler to ensure the code is efficient.

Conversely, Descend is a “safe-by-construction” imperative language. Inspired by Rust, Descend guarantees legal CPU and GPU memory management at compile time by tracking ownership and lifetimes. Following the previous example, we write matrix multiply in Descend:

// (Descend does not have releases; written on 12 April 2024.)

fn matmul<BLOCK: nat, i: nat, j: nat, k: nat, r: prv>(

A: &r shrd gpu.global [i32; i*k],

B: &r shrd gpu.global [i32; k*j],

C: &r uniq gpu.global [i32; i*j]

) -[grid: gpu.grid<XY<j/BLOCK, i/BLOCK>, XY<BLOCK, BLOCK>>] -> () {

sched(Y) block_row in grid {

sched(X) block in block_row {

sched(Y) thread_row in block {

sched(X) thread in thread_row {

let Ai = &shrd (*A)

.to_view

.grp::<k>

.grp::<BLOCK>[[block_row]][[thread_row]];

let Bj = &shrd (*B)

.to_view

.grp::<j>

.transp

.grp::<BLOCK>[[block]][[thread]];

let mut Cij = &uniq (*C)

.to_view

.grp::<j>

.grp::<BLOCK>[[block_row]]

.transp

.grp::<BLOCK>[[block]]

.transp[[thread_row]][[thread]];

let mut sum = 0;

for e in 0..k {

sum = sum + (*Ai)[e] * (*Bj)[e]

};

*Cij = sum

}

}

}

}

}

Lastly, we write matrix multiplication in CUDA, which follows the Single Instruction Multiple Thread (SIMT) programming paradigm. This low-level language can easily be mapped to the generated PTX, which shows how versatile it really is. Consider the naive square matrix multiplication below, where each dimension has size n:

__global__ void matmul(const int *A, const int *B, int *C, int n) {

int Ai = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int Bj = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int temporary = 0;

for (int k = 0; k < n; k++) {

temporary += A[Ai * n + k] * B[Bj + n * k];

}

C[Ai * n + Bj] = temporary;

}

In the example above, each thread loads one row of A and one column of B from global memory, performs an inner product, and stores the result to C. This naive implementation is memory-bound, i.e., no matter how fast the additions and multiplies occur, we will always be waiting on data movement. We can mitigate the overhead of global memory by using a lower-latency memory: shared memory. Note that this will require significant changes to the structure of our code: we need to rewrite loop bounds, update indices, synchronize threads, etc. This is demonstrated in the example below:

__global__ void matmul(const int *A, const int *B, int *C, int n) {

int Ai = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int Bj = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

__shared__ int shA[n];

__shared__ int shB[n];

int temporary = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += blockDim.x) {

shA[threadIdx.y * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x] =

A[Ai * n + i + threadIdx.x ];

shB[threadIdx.y * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x] =

B[Bj + n * i + threadIdx.y * n];

// Wait until all threads finish loading to shared memory.

__syncthreads();

for (int j = 0; j < blockDim.x; j++) {

temporary +=

shA[threadIdx.y * blockDim.x + j] *

shB[j * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x];

}

// Wait until all threads finish reading from shared memory.

__syncthreads();

}

C[Ai * n + Bj] = temporary;

}

This is just one of many optimizations to get a performant matrix multiplication kernel. We aren’t even considering multiple-level tiling, using Tensor Cores, etc. In some utopian setting, we wouldn’t need to, the compiler would do this automatically for us; in comes Triton.

What is Triton?

Triton is an imperative language and compiler stack to simplify the arduous process of writing GPU kernels. Antithetical to the SIMT model, users write programs that load, compute upon, and store blocks of memory. These blocks are accessed via a pointer interface. Then, the compiler automatically handles optimizations such as multi-threading, using fast memory, tensor cores, etc. So, the user must handle the outermost level of tiling, via loads and stores to global memory, and then the compiler handles the rest. The Triton website provides a comprehensive overview of the language with some concrete examples. For completeness, we provide a Matrix Multiply example:

@triton.jit

def matmul_kernel(

A, B, C, # Pointers to matrices

M, N, K, # Matrix dimensions

stride_am, stride_ak, # Stride parameters

stride_bk, stride_bn,

stride_cm, stride_cn,

BLOCK_SIZE_M: tl.constexpr, # Meta-parameters

BLOCK_SIZE_N: tl.constexpr,

BLOCK_SIZE_K: tl.constexpr,

GROUP_SIZE_M: tl.constexpr,

):

"""

Kernel for computing the matmul C = A @ B.

A has shape (M, K), B has shape (K, N) and C has shape (M, N)

"""

pid = tl.program_id(axis=0)

num_pid_m = tl.cdiv(M, BLOCK_SIZE_M)

num_pid_n = tl.cdiv(N, BLOCK_SIZE_N)

num_pid_in_group = GROUP_SIZE_M * num_pid_n

group_id = pid // num_pid_in_group

first_pid_m = group_id * GROUP_SIZE_M

group_size_m = min(num_pid_m - first_pid_m, GROUP_SIZE_M)

pid_m = first_pid_m + ((pid % num_pid_in_group) % group_size_m)

pid_n = (pid % num_pid_in_group) // group_size_m

offs_am = (pid_m * BLOCK_SIZE_M + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_M)) % M

offs_bn = (pid_n * BLOCK_SIZE_N + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_N)) % N

offs_k = tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_K)

As = A + \

(offs_am[:, None] * stride_am + offs_k[None, :] * stride_ak)

Bs = B + \

(offs_k[:, None] * stride_bk + offs_bn[None, :] * stride_bn)

accumulator = tl.zeros(

(BLOCK_SIZE_M, BLOCK_SIZE_N),

dtype=tl.float32

)

for k in range(0, tl.cdiv(K, BLOCK_SIZE_K)):

# Load the next block of A and B.

a = tl.load(

As,

mask=offs_k[None, :] < K - k * BLOCK_SIZE_K,

other=0.0

)

b = tl.load(

Bs,

mask=offs_k[:, None] < K - k * BLOCK_SIZE_K,

other=0.0

)

accumulator = tl.dot(a, b, accumulator)

As += BLOCK_SIZE_K * stride_ak

Bs += BLOCK_SIZE_K * stride_bk

offs_cm = pid_m * BLOCK_SIZE_M + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_M)

offs_cn = pid_n * BLOCK_SIZE_N + tl.arange(0, BLOCK_SIZE_N)

Cs = C + stride_cm * offs_cm[:, None] + stride_cn * offs_cn[None, :]

to_store = accumulator.to(tl.float16)

c_mask = (offs_cm[:, None] < M) & (offs_cn[None, :] < N)

tl.store(

Cs,

to_store,

mask=c_mask

)

Who uses it?

The Triton language and compiler stack is currently open source under OpenAI. Additionally, PyTorch 2.0 translates PyTorch programs into Triton in its new compiler backend, TorchInductor. Lastly, JAX uses Triton as a GPU backend target for its new kernel programming model, Pallas.

Strengths

Writing fast GPU programs is hard. For a memory-bound kernel, one must consider, at a minimum, the following:

- Memory coalescing (in global memory): thread access patterns are important to ensure we minimize the number of fetches.

- Memory hierarchy (global $\rightarrow$ shared $\rightarrow$ registers). Using a lower-latency memory is better, but requires synchronization and low-level instructions such as intra-warp shuffles.

- Bank conflicts (in shared memory): data structure layout is important to avoid bank conflicts, e.g., Array of Structures (AoS) versus Structure of Arrays (SoA).

For a compute-bound kernel such as matrix multiply or convolution, one must map instructions to Tensor Cores. This requires carefully choosing tile size, SM count, etc. Such optimizations are not always trivial; this can be illustrated by the number of NVIDIA Developer blog posts [1, 2, 3, 4, 5].

By performing block-level data flow analysis, the Triton language can automatically unlock optimizations such as memory coalescing, thread swizzling, pre-fetching, vectorization, instruction selection (e.g. Tensor Core), shared memory allocation and synchronization, and more.

Additionally, Triton provides a few other useful features, such as JIT compilation and auto-tuning support. In general, if you’re not the hottest GPU expert on the block and want to get fast, custom kernels for your application, then this might be the right tool.

Weaknesses

This is a performance savant’s worst nightmare: we ultimately become victim to a “black box” compiler that we can only hope will optimize our kernel. Worse yet, we don’t really have a way out. In other words, there exist optimizations that aren’t clearly accessible from the high-level abstraction of Triton. So, while Triton may be the right choice for quick iteration, it isn’t necessarily the best choice to squeeze out every drop of performance, i.e., it makes an important trade-off between productivity and versatility.

There is an alluring (yet slightly outdated Readers should be aware this was written when Triton 1.0 was released. I have run a few of these example kernels on Triton 2.1.0, and found they have improved since then, e.g., there is no longer unnecessary thread synchronizations in the reduction kernel. However, the post’s objective is still relevant: the Triton compiler is opaque. ) blog post by a senior engineer at NVIDIA, who inspects the emitted code from the Triton compiler, and reverse engineers the PTX back to CUDA (with the assistance of LLMs, no less).

Takeaways

- GPU languages should always have performance as one of their north stars. If the user didn’t want a fast program, then they could just use a CPU.

- There will always be trade-offs between safety, productivity, and versatility. These should provide guidance in the design of your language. For example, Triton is designed for fast iteration on neural network kernels, where “everything is a matrix multiply,” and fusion is an easy way to reduce memory bandwidth.

- A compiler provides automatic optimization, but can quickly become a burden for the performance engineer. This is highlighted by Mike Pall in a thread about the LuaJIT compiler. This is also a driving force behind the Exo Language, which attempts to externalize the compiler so that the optimizations are transparent.